About Troubadours

Modern-day troubadours

Nowadays we associate the term ‘troubadour’ with singer songwriters who not only write the lyrics and compose the music for their songs, but also often accompany themselves singing them. Because of the quality of their lyrics, many of these singer songwriters are considered not only singers and musicians but also poets, and their lyrics and melodies form a corpus which clearly defines their artistic persona. Depending on their cultural background or context, these singer songwriters tend to have a particular political affiliation (like the Nueva Trova in Cuba) or links with the folk music scene (especially in the US). This is why we associate modern-day troubadours with political protest or with community-based traditions. If we compare them with their medieval counterparts, we find that political activism is a trait common to their lyrics then and now; the modern ‘popular’ connotation, however, stems from a misunderstanding about who medieval troubadours were (see FAQ).

This is why music critics use the term ‘troubadour’ for a wide range of artists, such as Joan Manuel Serrat, Silvio Rodriguez, Bob Dylan, Leon Gieco, and Leonard Cohen. Among modern troubadours we also find groups who strive to give authentic performances of medieval troubadour songs, playing on period instruments and paying close attention to the original meaning of the lyrics and the medieval melody; or in other cases giving more personal interpretations influenced by current musical trends.

Who were the original troubadours?

Guillem de Berguedà, miniature from chansonnier I (13th C, Paris, BnF, fr. 854, f.192v).

Strictly speaking, however, troubadours are those writers who composed music and lyrics in the Occitan language during the 12th and 13th centuries. The earliest known troubadours were from the nobility, and their primary audience and main point of reference was the court. Although the central theme of their compositions was love, making their work a vehicle for the promulgation of the system of courtly values, the range of subjects, registers, and motifs employed by the troubadours is very broad and includes, for example, political commentary and humorous poetry.

The term 'troubadour' first appears in the work of Cercamon in about 1150, but by then Guilhem de Peitieu had already referred to his artistic activity as trobar and soon the use of trobador instead of poet, which was reserved for authors of Latin poetry, became widespread. Scholars do not refer to vernacular poets from the 14th century onwards as troubadours, but the troubadour legacy continued to exert a very strong influence on all European poetry (see spread).

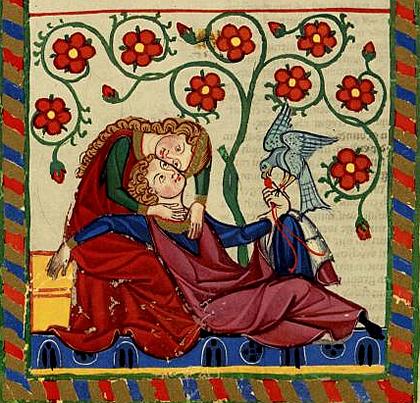

The Codex Manesse is the best known Minnesäng songbook (c.1300–1340, Heidelberg University Library, Cod. Pal. germ. 848). The miniature (f. 249v) shows the Minnesänger Herr Konrad von Altstettenv.

How important are they?

A group of vernacular poets might not strike us as being a particularly extraordinary phenomenon. Nonetheless, we have to bear in mind that when they started to appear (around 1100), high-status poetry in the Romance language territories was all in Latin. The only other works in the vernacular that might predate them were some epic or hagiographic pieces, almost all of which were anonymous. There is no doubt that the vernacular was the language used for the popular literature that must have existed, although no written traces of it have survived. The poetry of the troubadours is, therefore, the first example in Latin Europe of high-status poetry in the vernacular; that is to say, poetry written in a lofty register by authors with a high level of learning and interpretative skill. Evidently, the audience also had to have a high level of understanding (see poetics). Thanks to the troubadours, the vernacular language acquired a higher status and it started to be considered as prestigious as Latin, all the while attaining a degree of artifice that was the envy of classical poets (see troubadours as auctores).

In addition to its intrinsic value, troubadour poetry came to exert an extraordinary influence on the development of Western culture. The poets from the regions bordering Occitania, like Catalonia and northern Italy, adopted this style as their own and composed poems in Occitan over a long period of time. In other more distant areas, the troubadour style was also borrowed and adapted to local vernacular traditions, as happened in the courts of northern France with the trouvères, in Germany with the Minnesänger, and in Galicia and Castile with the trobadores. Even in pre-existing or yet more distant traditions, like the Scandinavian or Anglo-Saxon ones, the influence of the troubadours played a decisive role in their poetic and cultural evoltion.

An enduring influence

The troubadours are the progenitors of vernacular poetry in Europe, and their influence not only crossed political and linguistic frontiers, but also lasted for centuries. Their poetry was crucial in the development of the Renaissance, and their courtly ideology shaped an image of men, women, and love which spread throughout the European courts (see influence). Authors like Dante and Petrarch were directly influenced by them: they acknowledged the troubadours as the first high-status poets in the vernacular and held them in high esteem as their poetic forebears and models. In this sense, such fundamental works as Dante’s Vita Nuova and Petrarch’s Canzoniere show a clear indebtedness to troubadour poetry. Beyond the poetry itself, their courtly ideology also became a dominant element in narrative: it is the source of tales of ladies and love-struck knights, updated versions of which still abound, some reinforcing the image (there are countless modern variants of love seen as the submission of a man to an idealised women according to a set of values —aesthetic, moral, etc.— adapted to the prevailing paradigm, and of the ritual of seduction understood as a process), others deliberately breaking with the tradition and subverting the roles. The current worldview of love in a romantic sense is still undoubtedly in dialogue with the one created by the troubadours.

.jpg)

The god of love who is locking the heart of the lover in the «Roman de la Rose», written in part as an allegorical response to and representation of the troubadour ideology of fina amors, or courtly love (London, British Library, MS Add. 42133, f. 15r)

More on the troubadours, and a few names....

Who were these troubadours from Occitania who dazzled the European courts with their poetry? The first ones for whom we have documentary evidence were from the nobility: Guilhem, Count of Poitiers and Duke of Aquitane (1071–1127), Elbes II, Viscount of Ventadour (fl. 1096–1147), and Jaufre Rudel (fl. 1130–49), Prince of Playe (see [origins]). In fact, all levels of the nobility fostered troubadour poetry, from the lower ranks to the great monarchs, like Alfons I of Catalonia-Aragon (1154–96; known as The Troubadour), Pere the Great (1240–85), or Frederick II of Sicily (1296–1337). Even so, their role was more as sponsors and protectors of troubadours, and it seems, by and large, that they only performed as troubadours themselves occasionally. Although the first known troubadours were from the nobility —no surprise really given that we are talking about poetry of the court and for the court— we soon see the emergence of troubadours from a variety of different social backgrounds, reflecting the diversity of courtiers, but especially those who, because of their function at court, had the skills necessary to compose poetry of this type.

The vidas highlight an even greater diversity in naming knights, merchants, priests, burguers, and jongleurs as troubadours. Even some women of aristocratic birth composed troubadour poetry: these were known as trobairitz, and one of the most well known is the Countess of Dia (1140–75). While professional troubadours could perhaps make a living from their art (some appear to be active in only one court, with a single sponsor, while others were more itinerant), those who cultivated troubadour poetry more sporadically could be looking for prestige, a means to air different opinions, or to take part in a social game. Despite these heterogenous origins, troubadours had some awareness that they belonged to a tradition, and established a network of relationships among themselves, at times cordial, at times hostile, which transcended the strong medieval social barriers of status and gender, and which encompassed not only their contemporaries but also their predecessors (as can be explored in the map). The courts were the centre of promotion and protection for the troubadours and their poetry, and being a sponsor was considered a presitigious role for feudal lords.

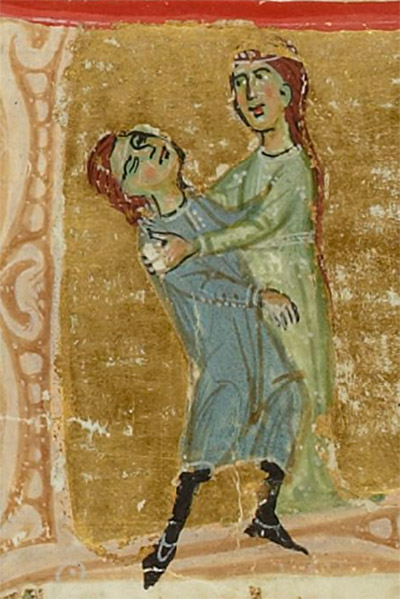

Na Castelloza, miniature from chansonnier K (13th C, Paris, BnF, MS fr. 12473, f. 110v).

Guilhem de Peitieu, miniature from chansonnier K (13th C, Paris, BnF, MS fr. 12473, f. 128r).

To sing, recite, or read?

What was this troubadour poetry which established the foundations of later European poetry like? Firstly, it was poetry to be performed, rather than read; in other words, it was meant to be sung before an audience. This is an essential characteristic of troubadour poetry and yet one of the trickiest problems with regard to modern-day performances: only one in ten melodies has survived, copied in manuscripts between one and two centuries after their date of composition, with musical notation that generally lacks sufficient information for us to be able to say for certain how it was performed (see music). A considerable part of the artifice of this poetry and the fundamental importance of rhyme and rhythm are linked to its musical setting. It is therefore understandable that the troubadour poetry genre par excellence, the most important one, with the largest corpus, is the canso or song.

A troubadour poem is made up of a series of metrical units, called coblas or strophes, that are sung to the same melody. The poet therefore has to calculate the line length strictly, and control the rhymes rigorously. There are then additional levels of complexity, such as the use of exclusively consonant rhymes, further internal rhymes —both within strophes and between them—, ensuring the same rhyme word is not repeated, and so on (see poetics). In addition to this formal complexity, troubadours composed certain pieces according to particular aesthetic styles, such as trobar ric or prim (with an emphasis on formal virtuosity), trobar clus (deliberately abstruse), and trobar leu (more accessible). These styles, however, are not just about aesthetics but also touch on matters of philosophy and ideology (see Di Girolamo 1989, ch. 4).

Another formal aspect that we should highlight is that troubadours strive to compose pieces that are perfect and unique: for example, the cansos have to have a new metrical and melodic scheme. The dialogue with tradition, from which they incorporate themes, motifs, and formal elements, together with their respect for metrical rigour and use of commonplaces according to the norms of medieval rhetoric, might make us think that they were composing rather impersonal pieces, lacking in originality. However, within these paramaters, the case is quite the opposite. Their works are characterised instead by diversity, contrasting opinions, the breaking of accepted, established schemes, all in order to create an original piece which highlights their individual troubadour identity.

.jpg)

Musical transcription of a piece by Guiraut de Riquer, from chansonnier R (14th C, Paris, BnF, MS fr. 22543).

Perdigon plays a stringed instrument, the rabel (chansonnier I, 13th century, Paris, BnF, MS fr. 12473, f. 36r).

Love, love, always love...

The main theme of troubadour poetry is love. The corpus of love poems is the largest and love is the central theme of the canso, the most refined troubadour genre, and the one most valued by the troubadours themselves. Furthermore, their treatment of love is an essential part of their cultural and literary identity: it represents a common framework, just as the formal traits do, with certain recurring elements; the troubadours engage with this framework and use it to express their own individuality. This love came to be known as fina amors or courtly love, and is formulated as love for a woman of high social standing, generally married to a feudal lord, a sensual love based on the extreme idealisation of an inaccessible woman and the submissive attitude of the troubadour lover, disposed to endure an apprenticeship designed to refine his behaviour and temper his emotions, in the hope of deserving the woman’s favours. The troubadours also engage with other themes of great importance for life at court, in particular those related to political or feudal affairs or to moral and doctrinal reflection. These questions are sung about in other genres, such as the sirventes, which uses the metre and melody of a preexisting piece (this calque is called a contrafactum). Works in this genre were used to present different opinions on a particular subject, as a vehicle for propaganda, as provocation or a positioning device in political conflicts, as satire and personal attack, to wade into a literary debate, to criticise customs and institutions, and so on. The tenso or the joc partit form a debate between troubadours via an exchange of coblas, a debate understood more as a social game than as a real argument or controversy. Other genres are the alba or dawn song, the pastorela, the planh or lament, and the dansa, which were incorporated into the system of troubadour genres later on. And it is worth bearing in mind that the self-awareness we see in the troubadour tradition does not exclude evolution: for example these genres emerge gradually, and the distinctions between them only become more pronounced from the mid 12th century onwards.

Miniature of Giraut de Bornelh with two jongleurs, chansonnier K (13th C, Paris, BNF, MS 12473, f. 4r).

Trobadours on the record

How was the poetry of the troubadours transmitted? Although troubadour poetry was composed to be sung, the level of artifice does not lend itself to improvisation (with the possible exception of certain games or debates in which the troubadours could demonstrate the speed of their ingenuity). It is thought that it was composed first on wax tablets and then the finished work, melody and lyrics, was copied onto parchment. An autograph manuscript was produced from which the jongleurs or minstrels would learn the piece by heart, or rotuli (scrolls) were made so they could perform the pieces at the courts addressed by the troubadour. Normally it was a jongleur specialised in musical and poetic performance who presented the pieces, accompanied on an instrument, although it seems that on some occasions the troubadours themselves performed their own works.

The beginnings of the legend...

How has troubadour poetry reached us? It has survived thanks to chansonniers or manuscript collections of troubadour poems, compiled especially in northern Italy from the mid 13th century, and later also in Occitania, northern France and Catalonia. In addition to the pieces themselves, some cançoners also transmit vidas and razos, short prose texts that introduced the poem(s) that followed: the vidas provided biographical data (real or fictional) essential for interpreting the troubadour’s work, while the razos explained the circumstances surrounding a particular poem. In this way, the cançoners, as well as transmitting at least a part of the corpus of troubadour poetry —composed in some cases more than a century before the cançoner was compiled— contributed to consolidating and immortalising the legend of the troubadours, based on the quality of their poetical work and its undoubted influence on what we today understand as European culture.

M. Victoria Rodríguez Winiarski (2017)